This is based on a case-study of Älvdalen, where two sets of Witch Trials took place in 1668, and of how the society moved past the terrifying events and found reconciliation. Read part 1 here.

It would be reasonable to assume that someone who had confessed to witchcraft would have a hard time finding a spouse, but that was not the case. Most of them did marry, and some just a few years after the hysteria.

There are even cases where former accusers and accused married each other. Gertrud Svensdotter was the first to be accused and in turn accused a lot of people. One of these were a young man named Lars Matson, who was tried in court but was acquitted. Less than five years later they got married.

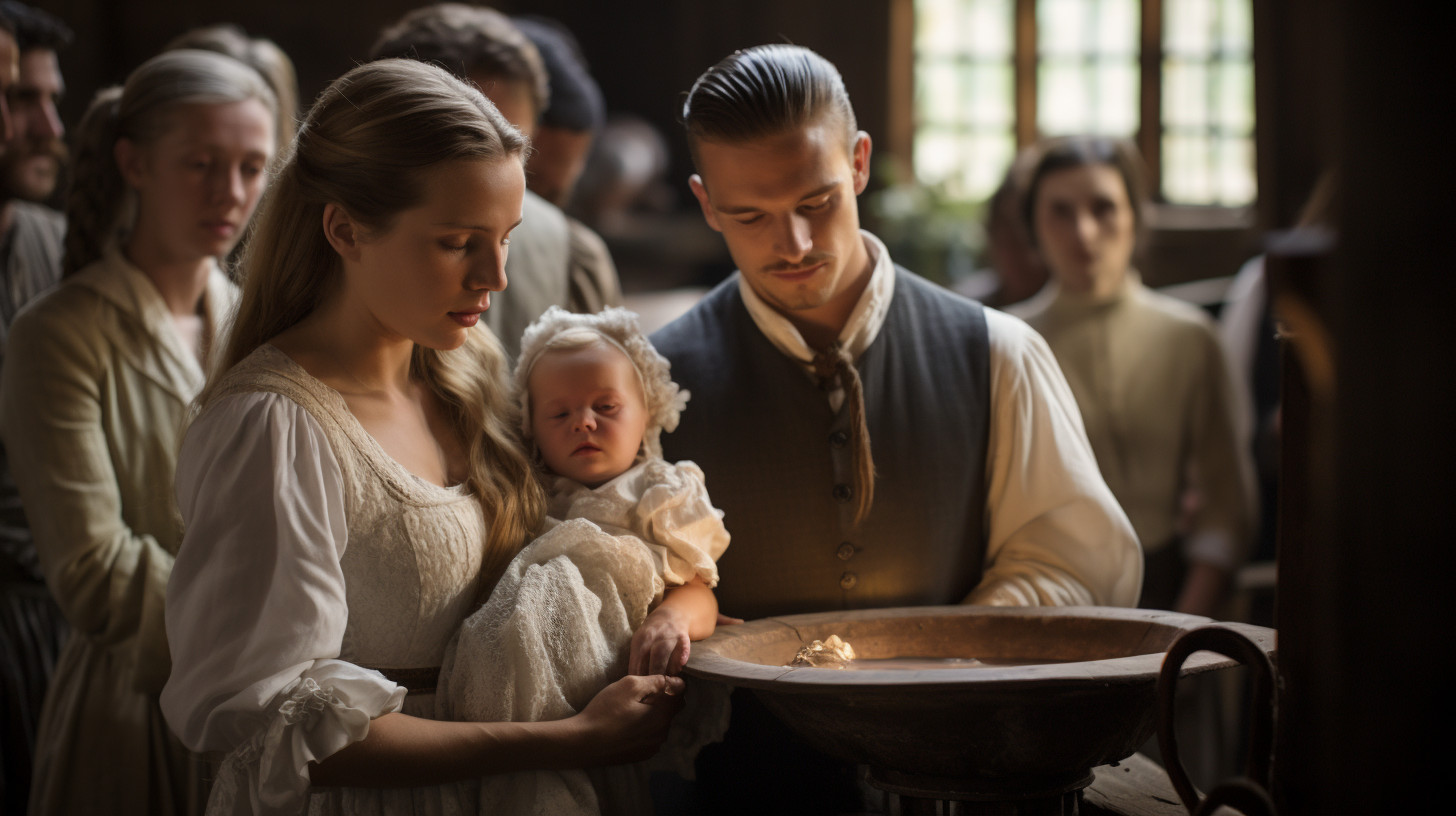

Another example of reconciliation in the society is that of Godparents. Since the Godparents’ role was to be responsible for the child’s Christian education, and you would think that those who had been accused of bringing children to Blåkulla and introduce them to the Devil should be banned from the role as Godparents.

Not so in Älvdalen. Marit Nilsdotter, who was sentenced to death but then paroled, became a Godmother in 1675. Despite being convicted of being a witch, just a few years later, she was deemed fit to be responsible for a child’s Christian upbringing.

In one of the prominent families, two brothers – Olof and Mats – had ended up on “opposing sides”, since Olof’s daughter Anna accused not only her grandmother but Mats’ wife and daughter of witchcraft. The grandmother, Marit, was executed and the aunt and cousin barely escaped with their lives. Anna herself was later executed as well.

If you believed Anna, her relatives had abused her in the worst way. If you didn’t, she accused innocent people, of which one was killed as a result.

But despite this, Mats became godfather to Olof’s son Lars in 1672. Maybe there was no ill-will between the brothers, or it was a conciliatory action.

These examples indicate that there was no resentment or enmity between the people of Älvdalen after the trials, at least not openly. And the whole society seems to have been working towards reconciliation and forgiveness.

But what about the grief, and the health of those who lost loved ones?

Many of them are mentioned in records as “crippled” shortly after the events. Crippled in this case probably meant too sick to work. An example is above mentioned Olof, who lost his daughter Anna.

The father, brother and sister-in-law of another executed woman, Elin, were all “crippled” in the years that followed her death. One can assume that the shock, grief, stress and in some cases guilt took its toll on their health.

A mother of a girl who was sentenced to public whipping, and who had been accused by her own brother, seemingly went into a deep depression.

So, in conclusion we can see a society that was deeply affected and scared by the events, but still refrained from further conflicts and actively worked to reconcile. Even convicted “witches” became re-integrated in society, and accuser and accused became godparents to each other’s children and even married each other.