Up until early spring 1543, everything had seemingly gone Nils Dacke’s way. Since midsummer the previous year, he had led the largest and most successful peasant revolt ever in Swedish history, known as the Dacke War (Dackefejden).

But the tide was about to turn…

The king, Gustav Vasa, had gathered many thousands of soldiers, both trained mercenaries and peasants from other parts of the country. They now massively outnumbered the rebels. Maybe some among Dacke’s followers began to doubt wether they could actually win, in the long term.

A severe setback for the rebellion was when one of Dacke’s main commanders, Erik Öning, switched sides. Perhaps he was enticed by an amnesty or reward, or he despaired of their chances of winning. With his defection, Dacke lost a large part of his army, while the king’s side gained important information about the peasants’ tactics.

The decisive battle took place at the end of March. Dacke and his men had tried to lure the king’s soldiers into a trap, but it had been discovered. Instead, they were forced into open combat, on the ice of a frozen lake, and there the peasants had no chance against the battle-trained soldiers.

Worse still was that Nils Dacke himself was wounded at the beginning of the battle when he was shot in both legs and had to be taken from the battlefield. After this, the battle degenerated into a slaughter.

When word of the peasants’ defeat spread in the area, many gave up, or switched sides. Dacke survived, but he needed time to heal and had to be kept hidden. Some of his commanders kept the fight going, and even had a few victories, but in most places, the spark of rebellion had gone out.

Even when Dacke recovered and tried to rally the locals to the cause, he was rejected. The people was sick of fighting, and the king’s men were everywhere. Almost deserted, Dacke and a few loyal men had to hide in the forrest.

During the summer of 1543, the king’s soldiers hunted Nils Dacke and his few remaining loyal men in the forests of Småland. Dacke did a few last attempts to raise a new army, but the people were no longer interested. Many of the rebels had been caught and severly punished.

In July, Gustav Vasa gave the people of Småland an ultimatum – find Dacke, dead or alive, or no grain would be sold to the district. Since the area was already ravaged and a lot of crops destroyed, the threat had an effect.

One of Dacke’s captains, Peder Skrivare, switched sides and offered to track down his former leader. Around the first of August, Skrivare and the king’s soldiers managed to track down Dacke in the forests. He allegedly tried to escape, but was shot in the back and died instantly.

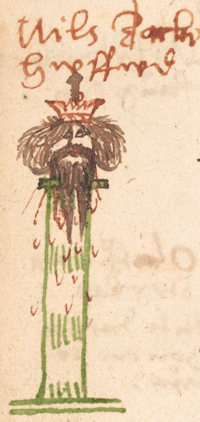

And it was probably lucky for him, had he been caught alive his end would have been very unpleasant. Now the bailiff had to content himself with putting his body to the wheel. His head was set up on a pillar with a copper crown on it. So ended the days of the greatest peasant leader in Swedish history. The rebellion died with him.

Småland was hit hard by the king’s wrath when he dealt with those who participated in the rebellion. Hundreds of people were fined or executed. Entire villages had to pay heavy fines to the crown. Dacke’s closest friends and family were executed, including his wife, son and brother-in-law.

The king wanted to make sure that the rebellion would not be repeated. But in vain. Because in the same areas, a new movement would soon arise – the Snapphanar.

The picture above is a contemporary sketch of Dacke’s severed head with the copper crown, painted by Joen Petri Klint.

Sources:

Adolfsson, Mats. Fogdemakt och bondevrede. Svenska uppror: 1500 – 1718. (2007)

Blom, Tomas. Dackefejden. Det stora upproret. (2019)